- Home

- J. L. Torres

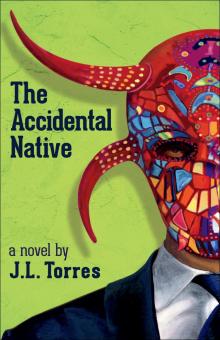

The Accidental Native

The Accidental Native Read online

The Accidental Native

a novel by

J.L. Torres

The Accidental Native is made possible through grants from the City of Houston through the Houston Arts Alliance and the National Endowment for the Arts.

Recovering the past, creating the future

Arte Público Press

University of Houston

4902 Gulf Fwy, Bldg 19, Rm 100

Houston, Texas 77204-2004

Cover design and art by William David Powell

Torres-Padilla, José L.

The accidental native / By J.L. Torres.—First Edition.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-55885-777-3 (alk. paper)

1. Parents—Death—Fiction. 2. Traffic accidents—Fiction. 3. Birthmothers—Fiction. 4. Puerto Ricans—United States—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3620.O62A64 2013

813'.6--dc23

2013022187

CIP

The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

© 2013 by José L. Torres-Padilla

Printed in the United States of America

13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Acknowledgments

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Acknowledgments

* * *

Many thanks to the Fulbright Program for granting me an opportunity to teach at the Universidad de Barcelona and Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. While on the Fulbright, I was also able to work on this novel. Special thanks to the Departments of English and German Philology in each institution. My Barcelona colleagues and friends, Cristina Alsina, Rodrigo Andrés and Raquel Serrano, I owe you so much for your hospitality, companionship and encouragement.

Thanks to my stateside friends and colleagues, Michael Carrino and Elizabeth Cohen for your insightful, thorough reading of early drafts of this novel. Your feedback helped tremendously; your encouragement and advice lifted me in moments of doubt. Thelma Carrino thanks for being such a great supportive friend. My colleagues at SUNY Plattsburgh, thanks for providing me with a wonderful, relatively sane place to work and grow.

I had the opportunity to receive encouragement and advice from Diana López and Selena Mclemore at the National Latino Writers Conference early in the process of writing this novel. Thanks to both of you and to the conference. David Powell, thank you so much for your artistic vision, designing gifts and patience. Lisa Sánchez González, Joanna B. Marshall, José Santos, thanks for your cover art feedback. My most appreciative thanks to Judith Ortiz Cofer, Ernesto Quiñonez, Ilan Stavans and Esmeralda Santiago for graciously offering their thoughts and comments on the novel.

This novel is set in Puerto Rico, not only geographically but emotionally. To my homeland and compatriots: I anguish with you until the decision that frees us. To those friends and colleagues who befriended me while living there, my warmest appreciation.

To those agents who passed on this novel but took time to offer constructive criticism, my sincerest thanks for your genuine comments that I incorporated into my revision.

My most profound gratitude to Arte Público Press for supporting Latina/o writers so they do not have to write to Peoria to be heard. To Nicolás Kanellos, your comments and edits made this novel better, and for that I am forever grateful. Un millón de gracias for having faith in my work. Gabriela Baeza Ventura, thanks for your meticulous reading of this novel and your spot on recommendations. Adelaida Mendoza, thank you for putting up with all my questions and anxieties. To the marketing and publicity crew at APP—Marina, Ashley and Carmen: you are the greatest; thanks for helping me to get out the word.

To the growing Latina/o reading population, thank you for supporting the literary voices of our communities.

As always, mucho amor y cariño to my wife Lee and sons, Alex and Julian, for your unconditional love and support, and for keeping my uprooted spirit grounded.

My deepest love to my mother, Marcelina Padilla, for always guiding me with her strength of character and moral fortitude; and my sister, Gladys and niece, Yari, por ese apoyo, siempre seguro. Thanks to my second familia: Celia López Vera, Ev, Big E, Lil and Mikey for the laughs, the big hugs and all that good food and love that goes with it.

Dedication

For every returning Puerto Rican;

and to those who remain unhomed.

Home is where one starts from.

T.S. Eliot

One

* * *

Sometimes your life runs like a film with a damn good script and you’re the lead. You’re hitting all your marks, and you’re not even finished with act one. That’s how it felt for me until she entered the scene like an extra gone rogue. After her, everything was upended, and I realized my entire life up to that moment had really been more like a movie about deception which had hit its major twist.

It all started with the violent, freakish deaths of my parents. They both swore they’d be buried in Puerto Rico. They belonged to that generation of Boricuas who grew up on equal helpings of rice and beans and nostalgia for Puerto Rico. They believed in the Puerto Rican Dream, which meant work in the U.S. to live your golden years in the island. So, they slaved to buy a house there but never returned, and they never did get around to buying a plot. Why would they? They were years from retiring, and too preoccupied with living. But I knew, because half-jokingly they made me promise, that if anything happened to them I had to step up and grant them that wish.

The funeral home in Jersey held them in their private morgue until I could buy a plot in Baná, their hometown. Erin drove me to the airport, where I made the classic request for “the next plane out”—in this case, San Juan. I had only opaque memories of Puerto Rico from a childhood visit, knew only the little my parents spoon fed me about it. How appropriate my journey into this new life of deception should start there. The Enchanted Island.

Picture a tropical paradise. Warm sunshine on happy faces focused on making you comfortable, accommodating your every whim. By the beach the ocean laps the sand as you drink the cool rum-spiked milk from a coconut dropped down to the ground by a sultry breeze. Everywhere you see bronzed, curvaceous women and Latin Lovers strutting half-naked along the inviting, turquoise water. Life is wonderful, swinging in your hammock, listening to the steady afro-Caribbean sensual rhythms stirring your loins.

Okay. Now, let’s take ourselves out of the tourism commercial and talk reality, or as the natives say, “vamos a hablar inglés,” let’s talk English. If you look at all the important national statistics—from unemployment to mortality rates—Puerto Rico persistently ranks low. And then you have the power outages, water shortages, work stoppages, the corrupt governments, the high crime rate, the lousy service you get most places you go, the horrific traffic and drivers, the increasing water and air pollution. Yet, every year Puerto Rico comes out in the list of the top five happiest nations. Puerto Ricans consistently say they a

re happy. The Puerto Rican avoidance strategy is to create a fantasy world and call it enchanted. But I didn’t know any of this. I was just going down to this tropical Disneyland to bury my parents.

The only place I could find to stay in the area at the last minute was a “fuck motel.” A place where you drive into a garage, out of nowhere someone closes the garage door, and you walk through a side door into a room without windows. The bed vibrates with a few quarters and if you want a “night pack” with toothbrush, toothpaste, condoms, you call and a few minutes later there’s a rap at the sliding window. It was half an hour from Baná.

At Baná Memorial Cemetery, the director told me that he had a few plots in the cemetery’s new extension, Monte Paraíso, and threw in a discount because he knew about my parents. He handed me a business card with the name of a local tombstone company. After I signed the paperwork and paid for the plots, he grabbed the phone to call the nearest funeral home. “I’ll take care of everything,” he said, patting me on the back.

My parents came from small families, and death seemed fond of both sides. Most of my few aunts and uncles had already passed on. Both sets of grandparents: gone (or so I thought). The one remaining uncle I knew, from all accounts was ill and feeble, suffering from Alzheimer’s. Cousins, I didn’t keep track of, couldn’t care less about the extended family thing, anyway. There wasn’t anyone to contact on the island other than my sickly uncle, Mario. No wake; they had waited long enough. So, I stood alone, dressed in ritual black, sweating like a pig over a roast pit, without as much as an umbrella for shade. My head was throbbing, my shoes sinking into mud.

Four cemetery workers lowered the caskets with canvas rope, one at a time, on top of each other, into a hole dug by the towable excavator parked a few feet away. Behind me, the director’s assistant held a corona, a complimentary crown of plastic flowers, which would be used again for another hurried ceremony later in the day.

Past them, under a large tree about a hundred yards back, a woman dressed in a smart pantsuit, appeared to be watching me, the entire scene, although I couldn’t tell for sure because she wore sunglasses. Even from that distance, she was the type of woman who stole your attention. But I didn’t make much of it. I just thought she was waiting for another funeral.

My mother often referred to Puerto Rico as “this little piece of patria.” I thought of that as I tossed a handful of dirt over their remains. The “house priest” had his concerned face on when he told me, “They’re in a better place.” I didn’t know about “better,” but they now slept in eternal peace in the muddy, undeveloped and barren extension of the municipal cemetery of this raggedy-ass town in central Puerto Rico. Right next to their neighbor for life, “María Lazos, 1920-2009.”

“Welcome home,” I whispered, shaking my head.

I shook the priest’s hand, thanked the assistant. Wiped the sweat trickling down my face, took one last look at the gravesite. The church bells rang three times. Game over, I thought.

Not knowing what else to do or where to go, I wandered into town.

I passed a couple of teens kissing on a corner, an older couple having a heated discussion, the wife waving a hand backwards in dismissal, a man scraping at a big block of ice to make snow cones, school kids fidgeting around him. At one point, I had the sensation someone was following me. Thinking back, did I see her slink into a small grocery store, hear her stiletto heels clicking on the sidewalk? I soon blended into the flow of faces looking like mine, but everything was foreign, distant.

I hit the plaza, drained and exhausted, and sat on a dirty, wooden bench. Mami claimed that as a young girl she had seen my father as a young boy in this very plaza and knew she would see him again. My father, the historian, called that improbable because his family had been established in San Juan for decades and only returned to their home in Baná during summers. Perhaps they never were here together at the same time, but for sure at some time both had individually stood here to watch pigeons waddling about, to people watch, to admire the majestic ceiba trees or to daydream about the future. As a group of children in school uniforms marched by, I started to cry, the back of a hand on my mouth, attempting to silence the sobs. The kids turned around, stunned at first, then started to laugh, pointing at me as if I were a freak.

The dark-haired woman, dressed in a navy blue pantsuit, scolded the children. They ran off, screaming and laughing. She walked over to me and slid by my side and offered tissues. As I grabbed them, she took off her sunglasses and I looked up to her eyes, red and teary, nervously scanning, almost devouring my face.

“I must look like shit,” I joked.

“You’re okay,” she said, rubbing my back.

I stared at her, my head askance. Her English was near native with only the thinnest trace of an accent. She panned my face with eyes entrenched in hardness; everything from the eyebrows to the few wrinkles framing the sockets signified a life of fighting, of burdening pain and hardships. Yet, at that moment, they softened just slightly so.

“I was at the cemetery.” She offered this as an explanation, but it only confused me more.

“I thought I was alone.”

“No, you were not,” she responded, defiantly. “I was there, right behind you.”

“I saw you,” I told her. “Did you know my mother and father?”

She lowered her head. “Yes,” she said, nodding. “Yes, I did.”

A longer pause. I returned some of the unused tissues and she wiped her nose.

“Long ago,” she told me, widening her fleshy lips into a smile. “Your father and I were together …”

I looked at her like she was speaking in tongues.

“It seems like another time and place.” Another smile, this one sad and lost. She dabbed at her eyes.

“No fuckin’ way,” I said, more to myself in a near whisper as I squinted at her like an apparition, trying to make sure she was real. But she heard me.

Her brows knitted; her eyes regained their hardness and pinned mine. Her reddened cheeks inflated, the fist brandishing soiled tissues in front of my face uncoiled a pointer finger.

“A little more respect,” she demanded.

I looked down into embarrassed silence.

And then she blurted it out.

I thought she was nuts. A fifty-something whack job with maternal yearnings who stalked vulnerable grieving orphans. And I was about to say “Okay, bitch, this is no time to be fucking with my head,” or something along those lines. But she pushed that piece of paper in front of me before I could say anything: the birth certificate. There they were: my name, her name, my father’s—all interconnected forever on that piece of paper. I kept looking at it, at her, shaking my head. Re-reading it until it got blurry. It hit me that every time I had needed a birth certificate for some official purpose, my parents took care of sending it to the right place. Too lazy and indifferent, I never asked why. Now, my head spun with anger, confusion, my throat and chest tightened by grief.

The woman took me by the arm and walked me over to a hole-in-the-wall diner by the plaza for coffee and a sandwich, the birth certificate dangling from my hand.

“In due time, in due time,” she repeated, “I will explain.”

I threw the certificate back at her. Stared at the sandwich, hungry but thinking I would retch if I took a bite.

“I know it’s a horrible time for you,” she said, folding the certificate back into her purse, “but fate has given me a little happiness by returning you to me.”

I shook my head, put up my hand for her to stop.

“Please, just give me a chance to know you, that’s all,” she said, giving me her business card with her home address and cell number scribbled on the back.

She took both my hands in hers, and brushed back my hair. I couldn’t look at her as she walked away, her heels clicking against the plaza’s stonework. I crumpled the card.

Two

* * *

The first time she called, I hung up. The f

ollowing calls, I didn’t answer. I just couldn’t. Her persistence and the sad-ass but optimistic messages she left made me finally cave in. Those early conversations were limited, guarded on my side, forced. Part of me grew to enjoy her calls, and then our Skyping, more than I wanted to admit, because my parents’ death, only a couple of months earlier, had left me a walking shell. But that connection with her would diminish minutes later as I wondered why a woman would abandon her baby son. What could possibly make her do that? Was she one of those career women who put ambition before her child? How selfish. How convenient to play the comforting mom after someone does all the work to raise your kid. And why didn’t my parents tell me? What were they hiding? What other secrets were they keeping from me? I started thinking this and would end up angry at their lie and betrayal. But then she would call again and our conversations flowed and all angry thoughts about not wanting to ever see this woman again would disappear. She would always end by assuring me that her home was mine, even suggesting the move to the island after obtaining my degree.

I didn’t want to attend graduation. It would remind me of my parents’ absence, of how alone I was. Once there, not even Erin’s loud presence cheered me up (she made enough noise by herself when my name was called to compete with any larger family contingent). In fact, her being there only made me feel worse—something I would never tell her, but it’s true.

Erin was, what, my “girl?” We had an on and off thing centered on sex and this illusion—delusion?—that opposites attract. She was blond, pale, with jade-colored eyes. Part Scottish, Italian—northern, she was fond of reminding me—and some Irish thrown in. She was in marketing, although she always introduced herself as a “designer” in the cosmetics field. Erin believed she had successfully bridged the creative-business divide and urged me to do the same: “put your writing skills to some use, go into advertising.”

The Accidental Native

The Accidental Native